Zero waste is an aspirational goal that is becoming more of a reality through a combination of policy, technology, and individual action, though achieving a true “zero waste” lifestyle remains a long-term ambition.

While “zero waste” refers to generating no waste at all, “zero waste to landfill” is a more immediate and achievable goal, where waste is diverted to reuse, recycling, or energy recovery instead of being buried. Initiatives like the UK's new Simpler Recycling regulations, a growing number of refill shops, and increased consumer demand for sustainable products are all contributing to this shift

Reliance on landfill in the UK is falling, but can the nation realistically achieve zero waste to landfill and bring about the end of landfill within the 5 years?

This article examines the latest data, policy signals and what England and Wales might do next — including how they could follow Scotland’s pending ban on sending organic waste to landfill. Read on for the evidence, timelines and practical steps people and councils can take.

Current Progress to Zero Waste to Landfill (2025)

The latest data from the Environment Agency (EA) show that reliance on landfill in England and Wales continues to fall, while inputs to other treatment facilities — notably materials recovery facilities (MRFs), anaerobic digestion plants and energy-from-waste (incineration) sites — have risen. This shift underpins the broader move towards zero waste approaches at local and national levels.

Overall waste arisings have remained relatively stable, but the tonnage sent to landfill has declined steadily since 2001. That decline in landfill tonnage in England and Wales reflects a combination of better sorting, more recycling and growth in treatment capacity over time.

Much of the early progress was enabled by sustained government investment in licensed treatment facilities and infrastructure during the 2000s, with many projects planned and funded before 2010.

Councils, waste companies and community groups have also played a role by piloting new collection systems and promoting reuse and eco-friendly products and packaging to reduce residual waste. For practical guidance on local action, see our get-started resources and local council reviews.

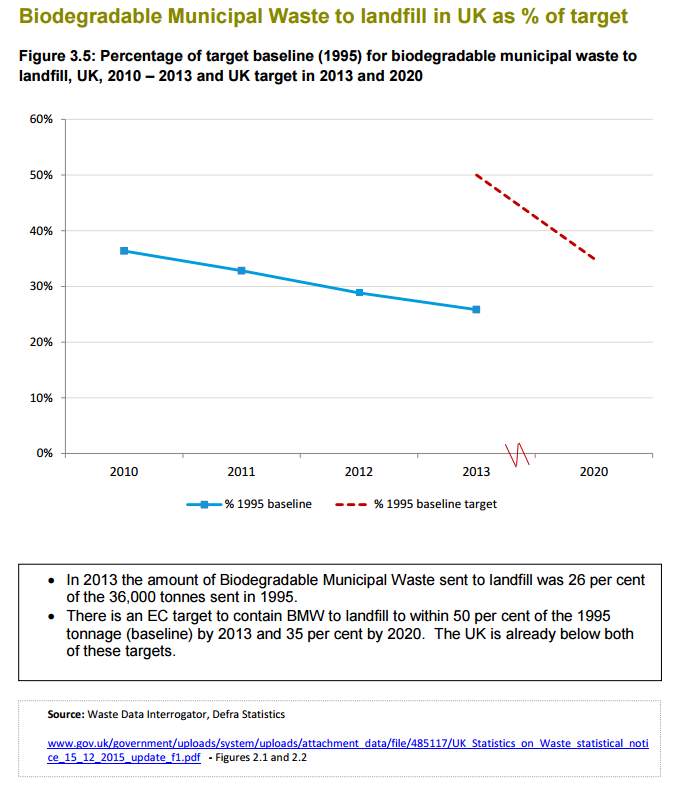

Evidence of the UK's Progress Toward the End of Landfill

Figure 1 (local authority collected waste management, England, 2000/01 to 2014/22) illustrates a clear downward trend in material sent to landfill. A simple linear projection of that trend suggests a possible path to zero waste to landfill within several years and possibly by 2030 — but this is an extrapolation by the author, not an official government forecast, and it carries substantial uncertainty.

For the underlying numbers, see the full report on this UK Government page. The chart below (sourced from the Government digest) shows recent annual landfill tonnages and helps explain why some commentators talk about the end of landfill in the UK — even though that outcome is not guaranteed.

Fig 1 – Local Authority Collected Waste Management, tonnages England, 2000/01 to 2014/22

“Local authority collected waste …” from www.gov.uk and used with no modifications.

Public opposition to local landfill sites remains strong, and many households favour policies that reduce landfill because of perceived risks such as water pollution from older sites. Reducing biodegradable municipal waste and increasing diversion to MRFs, anaerobic digestion and energy-from-waste are practical ways to cut landfill tonnages. If you want to act locally, get started with simple steps to cut food waste, improve home composting and support council collection changes.

But, Showing a Trend, Doesn't Mean “Zero Waste” Will Ever Happen…

Can a falling line on a chart be taken as proof that the UK will reach zero waste to landfill? Not necessarily — trends can be interrupted by policy shifts, capacity constraints or market changes.

The obvious questions are:

- Is this apparent progress really so close to becoming reality when built infrastructure and funding cycles are considered?

- Is it credible to claim that the UK will never need additional landfills in future, given regional imbalances in capacity and long lead times for new facilities?

Read the evidence below to see why a simple projection can mislead and what factors could change the way the decline in landfill tonnages plays out.

Not The End of Landfill…

CC BY by cogdogblog

The political and funding environment since 2010 has altered the trajectory of waste infrastructure development. Austerity measures and changes to procurement rules for public-private partnerships (PPPs) reduced capital flows into new waste treatment contracts, slowing the rollout of facilities that divert waste from landfill.

Many of the treatment projects delivered in the 2000s were the result of a decade of planning and public investment. When that pipeline of investment largely wound down by around 2012, fewer new materials recovery facilities, anaerobic digestion plants and energy-from-waste projects reached commissioning. Because these facilities typically take five to ten years from planning to operation, the withdrawal of funding is only now affecting landfill tonnages.

In short, the slowdown in new diversion capacity helps explain why the earlier rapid decline in landfill tonnages has levelled off in places. The lead time for new infrastructure is long, and councils and waste companies need predictable capital funding and clear procurement routes to deliver further diversion at scale.

Policy signals matter: without renewed public investment or commercially attractive delivery models, the decline toward zero waste will stall. If you are a campaigner or councillor, ask about local procurement plans, timelines for new diversion facilities and whether organic waste collections are scheduled — practical questions that can help accelerate progress.

Ultimately, unless circular economy policy and investment return at pace, expect waste sent to landfill to stagnate rather than continue a steady fall; reversing that will take time, funding and a clear supply chain for recyclables and organic materials.

Can the Trend of Falling Waste to Landfill Continue and Will All UK Landfills Cease?

Based on the publicly available data at the time of writing, there is no official UK government forecast stating that landfill will end by 2030; no formal assessment sets expected annual landfill tonnages for that year. Given the continued presence of residual streams and the lead times for new diversion infrastructure, it is reasonable to expect a non-zero tonnage to still be going to landfill in 2023.

This absence of clear direction from the national government needs to be addressed with renewed investment and policy signals if England and Wales are to meet public expectations for a move towards zero waste.

Scotland’s pending ban on sending organic waste to landfill is a useful comparator here: it shows a concrete policy route that could be followed, by phasing in separate food and garden waste collections and building the necessary anaerobic digestion and composting capacity.

If you want to influence the pace of change locally, get started by reviewing your council’s waste strategy, asking candidates or councillors about plans for separate organics collections and sharing practical steps to reduce household waste.

Collective public pressure and informed local campaigning remain powerful ways people can push for the infrastructure and policies needed to accelerate a transition away from landfill.

Fig 2. Waste Tonnages of the UK Nations 2010 to 2023

“UK statistics on waste – GOV.UK” from www.gov.uk and used with no modifications.

Does the UK Have as Much Landfill Capacity as it Will Ever Need, or will The UK Soon Need New Landfills?

In 2008, the UK Government / Environment Agency estimated that, given lower demand and modest capacity increases, England and Wales had an average of around seven years' tipping space remaining (CIWM Members Journal, May 2008).

That projection implied a risk of running low on capacity by about 2015 — a scenario that did not materialise nationally. The divergence reflects a mix of demand reduction, changing accounting methods, exports and local variations in supply and remains a reminder that capacity forecasts can be sensitive to policy and market shifts.

The Pressure for New Landfills Will Start in the South East

The landfill need is not evenly distributed. The so-called “London effect” means the East of England, London and the South East operate nearly as a single waste market and historically faced tighter local tipping space.

At the time, that area was forecast to have only around five years' tipping space remaining, although actual local circumstances have since varied.

Meanwhile, landfill capacity has tended to be greater in the Midlands and North East, with Wales slightly above the national average.

Regional factors such as transfer stations, haulage routes and the availability of suitable sites can delay the need for new facilities in some areas while accelerating it in others. A clear, updated regional view of capacity versus demand (with current figures) is essential for planning whether new landfills will be required and where.

Fig. 3 – UK Waste Types as a Percentage of All UK Waste

“UK statistics on waste – GOV.UK” from www.gov.uk and used with no modifications.

The End of Landfill?

Future landfill capacity depends on two things: how much waste is produced and diverted, and how many permitted facilities (and active cells) are available to receive any residual material. Waste arisings have broadly stabilised and less is being sent to landfill than two decades ago, but that does not automatically mean landfilling will end.

In the mid-2000s, there were nearly 9,000 waste management licences of various kinds, of which under 20% related to landfill; active landfill sites were a much smaller subset (historical figures cited in earlier reports put active landfills at fewer than 600 in that period).

Those licence and permit counts have since changed and should be checked against the Environment Agency’s current register for an up?to?date view.

The EA suggested in 2008 that there might be a small increase in landfill capacity, yet new landfill permits have been rare in recent years (for example, only a handful of new landfill licences were recorded in the mid-2000s). That limited growth in permitted capacity, combined with a steady rate of disposal for remaining residual streams, means demand for landfill will not disappear overnight.

Policy implications: even if the volume of waste sent to landfill falls, councils and private operators will still need contingency capacity and clear licensing pathways.

Expect demand for landfill to continue at a lower, but nonetheless significant, level after 2023 unless investment in diversion infrastructure — recycling, anaerobic digestion and other treatment facilities — accelerates. For planners and campaigners, monitoring licensing data and active cell capacity gives the clearest local view of when new facilities might be required.

New Landfills Will be Needed after 2025

Given the current pace of investment in waste processing, reuse and recycling, it is likely that some new landfill capacity will still be required beyond 2025.

Achieving full zero waste to landfill would demand sustained capital spending on local authority and commercial treatment facilities, including expanded recycling systems, anaerobic digestion for organics and improved separation infrastructure — and those projects take many years to deliver.

Predicting a precise date is difficult; the earlier statement that zero waste in the UK is unlikely before 2030 should be read as an informed estimate rather than a guarantee. It rests on lead times for new infrastructure, the scale of public and private funding required, and uncertainty over national policy direction.

Brexit and consequent regulatory shifts have altered the policy drivers that previously pushed the UK toward faster change, and post-EU dynamics may affect the timing and nature of future investment.

Scotland’s pending ban on sending organic waste to landfill is a concrete example of a policy that forces infrastructure change: it requires separate food and garden waste collections and sufficient anaerobic digestion/composting capacity.

England and Wales could follow that route, but doing so would need clear national mandates, funding for rollout and time to build processing capacity — a process measured in years rather than months.

If you want to help accelerate the transition, review your council’s waste strategy, support campaigns for separate organics collections, and contact your MP to ask about plans for funding and delivery.

Local pressure combined with robust commercial models for collection and treatment is the most practicable way to reduce landfilling and move toward a greener, low-waste future.

Zero Waste or a Minimum Demand for an Internationally Acceptable Waste Policy

Will public opinion alone, after leaving the EU, be enough to push the UK towards an internationally acceptable waste management policy, let alone full zero waste? At present, that remains an open question.

Public opposition to local waste facility development — landfill, incineration or large energy-from-waste plants — remains a powerful force. That NIMBY sentiment has contributed to a sharp reduction in planning applications in many areas, and, since 2008, new landfill licence applications have been rare.

Commercial factors also play a part. With excess landfill capacity and weak returns, many waste companies paused investment in new landfill infrastructure. As remaining sites fill and competition for available waste increases, commercial incentives to develop new sites will rise — creating future pressure for new facilities.

Key stakeholders include local authorities (who plan collections and contracts), waste operators (who manage treatment and disposal), national government (which sets policy and funding), and the public (whose views shape local consent).

Case studies of recent planning disputes illustrate how these interests collide; sharing local experiences in reviews and community forums can help build constructive solutions.

If you have direct experience of a local planning debate over a waste site, share your view in the comments and consider contacting councillors to ask how operators plan to deliver low-impact, eco-sensitive solutions that minimise traffic, packaging waste and risks to watercourses.

The Verdict on Zero Waste in England and Wales – Not Before 2030 if Then…

The central question remains: will the continuing decline in landfill numbers and tonnages drive the UK to an end of landfill — and if so, when? Based on current policy signals, investment levels and infrastructure lead times, the short answer is no: a nationwide move to full zero waste to landfill is unlikely in the near term and, if it happens, it is more plausibly a 2030s outcome than one before 2030.

The simple answer is, not in the short-term, and, to misquote Mark Twain:

“reports of the death of landfill are greatly exaggerated.”

Key takeaways: data show real progress on reducing landfill, but policy gaps and stalled investment slow the transition; Scotland’s pending ban on sending organic waste to landfill is a model for how England and Wales might accelerate change; and regional capacity imbalances mean some areas will need contingency landfill capacity for longer.

What you can do

- Get started at home: reduce food waste, separate organics where possible, and choose products and packaging with lower impact.

- Check your council’s waste strategy and sign up to local reviews or consultations to push for separate organics collections and better recycling services.

- Contact your MP or local councillors to ask about funding and timelines for diversion infrastructure — public pressure helps prioritise waste investment.

If you want updates, follow our coverage and reviews on local policy changes and practical steps to support a move away from landfill.

[Article first posted July 2016. Updated October 2025.]